Toilet tourism in Kenya

— Blog Post — 4 min read

Greetings from Kenya! For most of the past week, I have not so much been in Kenya as I have been in a hotel in Kenya, meeting with other members of the international toilet diaspora at a convening organized by the Gates Foundation. On Tuesday, however, we all spread out for a day on one of three field trips, and naturally I chose the visit organized around rural sanitation. I am generally pretty skeptical about official field visits – usually, it is mostly an opportunity to learn about official organizations and officialness – but, perhaps because I know so little about Kenya to begin with, this time I felt I was taking away some important lessons for our work back in India.

The most immediately striking contrast with rural U.P. was the wide open spaces and the low, low population density. Population density is important for sanitation because the closer children are to environmental germs, the more likely they are to find them and get sick. I often say that in rural Sitapur it is hard to find a place to stand outside where you cannot see another person. We had no trouble driving past green vistas to scenic spot after spot where most of the people in sight were the folks we brought with us.

We visited Naivasha, and I don’t know nearly enough about Kenya to know how representative my experience was, but it certainly was striking: it is one thing to read population density numbers, and quite another to feel it. Our second village visit felt as empty—and as scenic – as a national park…and indeed was much less full of people than the national park Diane and I visited last spring in Kerala!

The next contrast I noticed was the apparent satisfaction with what, in Hindi, we would call kaccha latrines (the word literally translates “raw”): informally made latrines, assembled out of organic or local material. This is in contrast with pukka latrines, formally constructed out of bricks or cement. As you saw in Diane’s recent post about her fieldwork in Haryana, when we do happen to find latrines in rural north India, they are almost always quite pukka. The policy discussion in India, especially in Delhi, is almost exclusively focused on expensively constructed latrines; for example, one group here at the Gates convening presented their work on a program attempting to sell $200 pukka latrines in rural Bihar.

The standard argument – which appears to be true – is that too many people in India simply don’t want kaccha latrines. One interpretation of this is that many of them actually don’t want latrines at all, and are only willing to put up with one if it comes in the form of a fancy asset. But the parts of Naivasha that I was taken to seemed to be a different story. People had – and used – latrines that amounted to little more than covered holes in the dirt with walls made out of sticks and plastic bags. Lest I be misunderstood, that’s great! Widespread use of such simple latrines has helped increase average child height in Bangladesh; earlier this week I saw new evidence from a randomized experiment showing that such a basic step away from open defecation helped children to grow taller in a project in Mali.

[caption id="attachment_1199" align="aligncenter" width="480"]

the outside view of a simple latrine[/caption]

the outside view of a simple latrine[/caption]

The picture above shows one of the latrines we saw. We asked a local woman we had met nearby if she was really perfectly happy with her latrine – if she really had no improvement that she wanted to make. She assured us, to our fascination and gladness, that she was perfectly happy with her simple latrine. In a classic bit of comedy (“Does your dog bite?” “No.” … “Ow! You said your dog didn’t bite!” “That is not my dog.”) in the van back to Nairobi we subsequently realized that we weren’t exactly sure that the latrine we were looking at was indeed her latrine. Although this certainly illustrates the dangers of doing fieldwork in a language that you do not understand, to me, the existence of that kaccha latrine itself was proof that Naivasha is a different sanitary world.

[caption id="attachment_1201" align="aligncenter" width="480"]

inside the same simple latrine[/caption]

inside the same simple latrine[/caption]

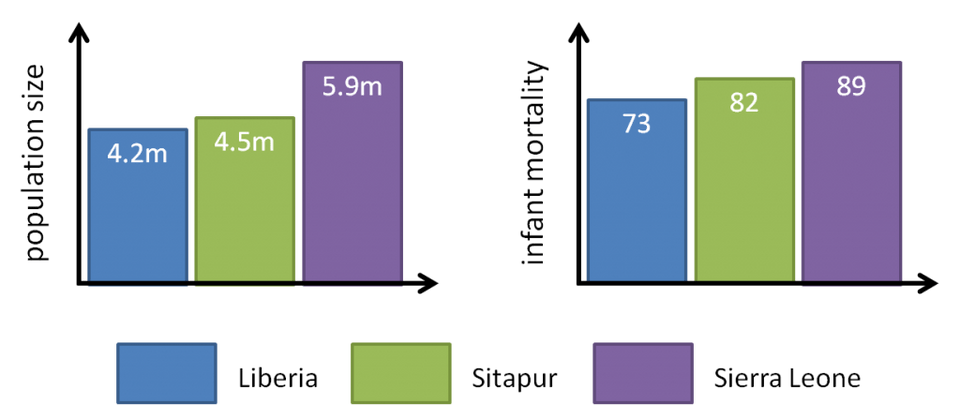

My last lesson came from statistics, as I was sitting in an office in Nairobi yesterday, participating in a discussion of the importance of sanitation for infant and child mortality. Somebody brought up the high infant mortality rates in Sierra Leone and Liberia, citing figures that seemed a little too high to me. Sitapur district is only one of over 70 districts in Uttar Pradesh, and about 600 in all India, and is noteworthy in this context only because it is the site of our rural home. I realized that, with a population of 4.5 million people, Sitapur falls squarely between the 4.2 million and 5.9 million that Google reports for Liberia and Sierra Leone, respectively.

So, Sitapur is about the size of these African countries. How does its infant mortality compare? According to the DHS app on my ipad, 73 per 1,000 babies born die before their first birthday in Liberia, and 89 do in Sierra Leone. Sitapur, according to the Annual Health Survey, is again in the middle, with an infant mortality rate of 82. Moreover, according to the same AHS data, out of the only nine states surveyed, 18 other districts suffer infant mortality as high as Sitapur’s or higher, and 8 of these cases exceed even Sierra Leone. Of course, there is nothing making Liberia or Sierra Leone especially appropriate comparison cases; they just happen to be what came up in conversation.

Economists and political scientists have theorized and cataloged the disadvantages that a country inherits from the arbitrary colonial carving of artificial national borders. I would be interested in the same scholars’ reflections on the consequences of the inattention a population receives from not counting as a country at all.

[caption id="attachment_1196" align="aligncenter" width="300"]

an insightfully titled slide from the conference[/caption]

an insightfully titled slide from the conference[/caption]