The most dangerous thing that humans make?

— Blog Post — 3 min read

What is the most dangerous thing that humans make? Is it nuclear weapons? Is it carbon emissions? To be honest, I don’t know (and I’m not particularly sure how we might even find out), but I would like to propose a candidate that may well be the worst: poop.

As the children’s book reminds us, everyone poops. Yet, it’s understandably something we tend to avoid talking about. This avoidance is relatively easy in rich countries: we flush the toilet and, as near as we can tell, the world is just the same as it was before we got started. But, in places without such nice facilities, everyone poops means poop everywhere.

So – as authors Maggie Black and Ben Fawcett persuaded me in their 2008 book The Last Taboo – we must stop avoiding talking about poop. And, in particular, we should avoid talking euphemistically about access to safe water when we really mean access to a good place to put poop.

Poop is a strong contender for “most dangerous substance” along at least two dimensions: there is a lot of it, and it makes people very sick. As Kosek, Bern, and Guerrant estimated in 2003, “diarrhoea accounted for a median of 21% of all deaths of children aged under 5 years in [poor countries], being responsible for 2.5 million deaths per year.” That is a lot of sick children, and as we have seen before in this blog, the ones who survive miss out on the calories and nutrition that the diarrhea cost them, lastingly hurting their physical and cognitive growth and health.

So, where does poop go in India? I’ve been looking into that using the India Human Development Survey, the representative sample of over 40,000 households. The astounding answer is that in about half of Indian households, people simply go outside and poop. They have no toilet or latrine, not their own and not access to a shared one. They simply go. In the academic development literature, this is called “open defecation.”

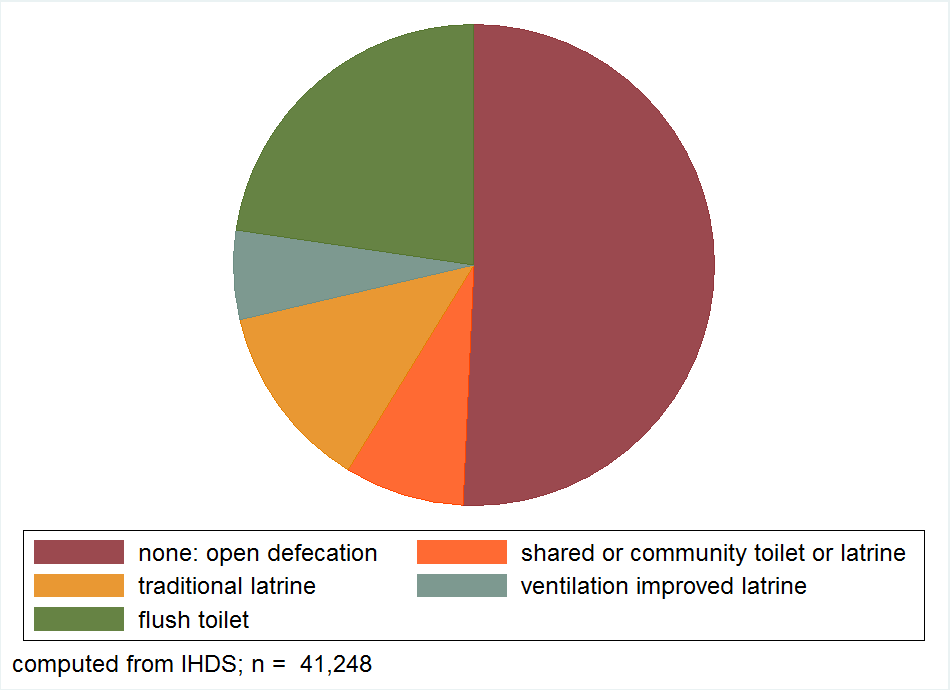

The pie chart reports the statistics. Less than a quarter of households have some sort of flush toilet; another quarter either owns a latrine (a pit for poop) or has access to a shared facility. That leaves half – the large red slice – with nowhere in particular to go. In this environment, it is no wonder that diarrhea gets around.

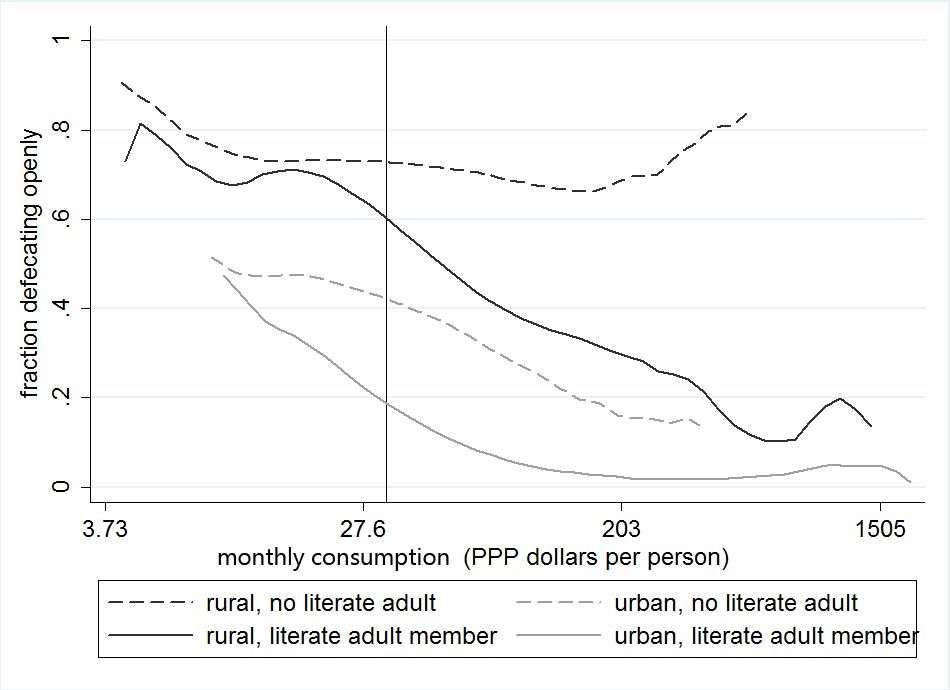

We can look a little more closely at these statistics. This graph plots the fraction of households openly defecating at different consumption levels, separately for rural and urban households, and for those that do or do not have at least one literate adult. I constructed this “open defecation” variable from the pie chart: it indicates people who do not have access to one of these other kinds of toilet or latrine. (You can click on the graph for a bigger image):

Open defecation is more common in rural areas than urban areas, but it is also less harmful there, where people are less densely living together. Among literate urban households, open defecation has been pretty much eliminated for those whose consumption has reached $200 per month. On the other hand, even among the (relatively) richest illiterate rural households, open defecation remains common, practiced in 80 percent of households. The vertical line marks the international poverty line of $1.08 per person per day sometimes used by non-profits and governments. This is a pretty low standard for being out of poverty, and even at it 60 percent of literate rural households and 20 percent of literate urban households are openly defecating in India. Having a place to poop seems like it would be a high priority, but at a dollar a day, other needs get in the way.

These statistics are dramatic, and perhaps back up my suggestion that poop is so dangerous. But they do not take us very far towards knowing what to do about it. The next step is to understand why people must poop in the open, and under what circumstances. I’ve recently been looking at the effects of inequality within Indian villages. Preliminarily, it seems that in villages where the local rich are even (relatively) richer, open defecation is more common. This paradoxical trend may be because the elite can buy alternatives to public water and health systems, so they do not invest in them; or it could be because the poor, at a greater social distance, are less influenced by the hygiene practices of the rich. Or, it could reflect some other explanation altogether. This does suggest that, as India continues to grow unequal, this inequality could be unhealthy for everybody.