SQUATing in Nirmal Gram Villages in Rajasthan

— Blog Post — 2 min read

A few days ago I went with our SQUAT survey team to a village in Tonk, Rajasthan. While walking into the village, I saw a girl of around 8 walking out into the fields off the side of the road with an old plastic bottle filled with water. She was going to defecate in the open. And after spending the whole morning there, I noticed she was not the only one. In short, to me the village seemed like it was like many others that we had already visited in the district.

But when I met Aashish for lunch, he told me that the village was in fact not like the others that we had already visited, that it was open defecation free! Or at least was ODF in the eyes of the government at one point in time.

[caption id="attachment_1231" align="aligncenter" width="480"]

The sanitation campaign is here, we’ve made our village open defecation free.[/caption]

The sanitation campaign is here, we’ve made our village open defecation free.[/caption]

Aashish can do many things that I can’t do very well, and one of them is reading Hindi quickly. While he was walking around the village accompanying our surveyors on interviews, he noticed wall-paintings like the one above saying that the village had won the Nirmal Gram Puruskar (NGP), a monetary prize awarded to GPs that have eliminated open defecation.

However, the village was clearly not open defecation free. Of the nine randomly selected households with which our team conducted interviews, only four had latrines. Of these four, all of the members of two households still defecated in the open despite saying they had a latrine. So of the households we visited, only two had latrines that were used, but not by everyone; some of those still reported going in the open regularly.

In one of the households that I visited with Laxmi, one of our surveyors, our respondent told us that her household had a latrine and that the sarpanch had built it for them. But when we went to the latrine to complete the observation section, we realized that although it had been a latrine at one point in time, the household had removed the seat and filled in the pit with cement. There was no roof or door, and it looked to me like they used it to urinate and/or wash clothes. Our respondent told us that they had filled in the pit because there was so much space to go in the open. Indeed, they lived on the edge of the village and could easily go in the fields next to their house. I also suspect that the respondent thought that the latrine was too close to their living quarters, in fact it was right next to the one kaccha room in the house. Many people in north India believe that it is impure to have a latrine close to the living quarters, and in fact our respondent believed so as well. She believed that latrines should be built far from the house, and anywhere closer is impure.

[caption id="attachment_1230" align="aligncenter" width="480"]

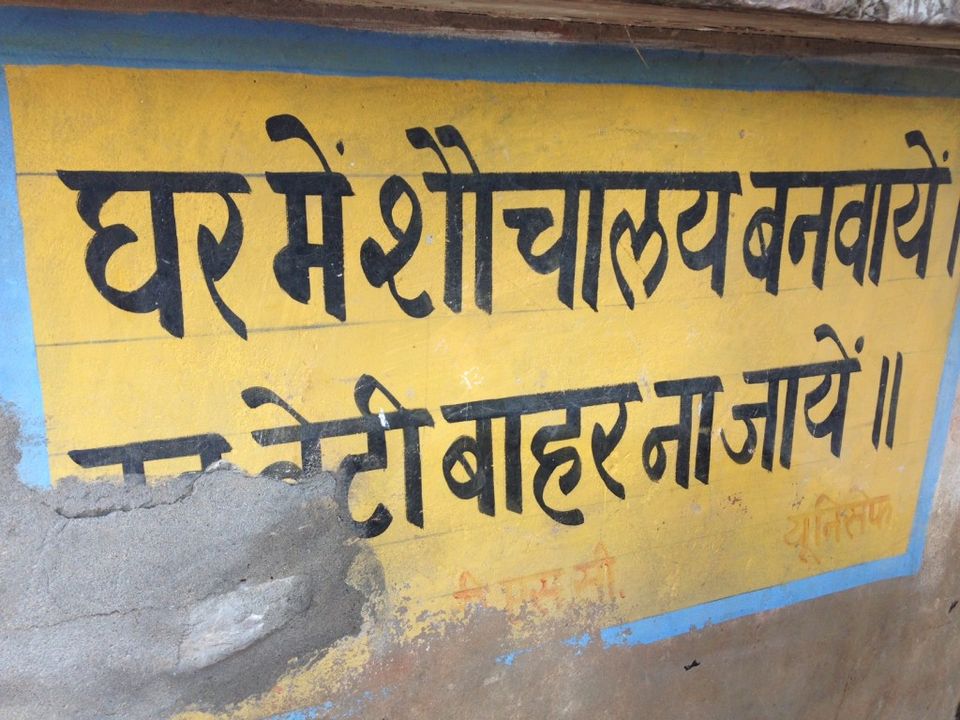

Build a toilet in your house, and your daughters and daughters-in-law won’t have to go outside.[/caption]

Build a toilet in your house, and your daughters and daughters-in-law won’t have to go outside.[/caption]

There had clearly been a sanitation campaign in the village; some of the poorer households (the one we visited was quite poor) had gotten latrines from the sarpanch. And there were old slogans written on the walls throughout the village. However, the messages written on the walls clearly did not sink in and the latrines built were clearly not always used.

This just shows how important the behavioral component of this problem is, and how difficult it is to change. Building latrines alone will not solve the problem. The NGP has the right goal in mind, incentivizing the use of latrines, but this only has the potential to work as an incentive if it is awarded to villages that really do sustainably eliminate open defecation.