Smoke gets in whose eyes?

— Blog Post — 3 min read

For the past month and a half or so, Diane and I have been in Delhi. We've made friends with the great people at the Delhi School of Economics and with the folks at NCAER who bring you my favorite survey, the India Human Development Survey (ihds.umd.edu). But tonight Avinash arrives in Delhi from Boston, and tomorrow the three of us head out: first to Bihar, then the Madhya Pradesh. We'll be looking for a rural homebase for RICE, and we're excited about getting back to this sort of work. We haven’t written as many blog posts as we should have, and with any luck our travels starting tomorrow should bring posts about the people we meet – probably more fun than our usual posts about graphs.But today, I have one more graph for you.

· · ·

Many families in rural India cook their food over an open fire every day.They typically use what are called “traditional” or “biomass” fuels: that is, firewood or dung cakes.The trouble is – as anyone who has made s’mores knows – burning these fuels produces lots of thick, dark smoke.Usually, the women who are cooking over these fuels are doing so in a small, indoor kitchen, often in a house made of mud with little ventilation.So, they end up breathing in much of this deadly smoke – or, as health researchers call it, “indoor air pollution.”

Some households, however, use cleaner cooking fuel, such as propane or gas.Why don’t more families use these cleaner, healthier fuels?One reason, of course, is price, but clean cooking fuels are more available in India than ever before, and price cannot explain all of the variation in who uses clean fuel.

Avinash and I realized something that many people – including half a billion Indian women – already knew too well: because Indian women do almost all of the cooking, they are the ones who breathe in the smoke.Moreover, there is much gender inequality in India; in most households in India, women have much less power than men.This suggests one reason, among many, why some households don’t use clean fuel: women suffer most from the dirty fuel (either breathing in the smoke, or having to collect the wood or dung), they have the least say.

So, we next wondered how to capture this statistically: how could we use data to test whether a woman having higher status – that is, more power and higher social “rank” – within a household makes it more likely to use clean fuel?Many researchers have asked that question before, but it has proven difficult to convincingly answer.The problem is that household with higher-status women are also different in other ways – typically richer, better educated, more urban – so it is hard to say what difference causes the “effect.”

We needed a statistically observable reason that some women would have lower intra-household status than others, a reason that wouldn’t plausibly have anything else to do with what type a fuel people use.The answer was that gender bias in India has consequences beyond cooking fuel.In particular, most families would much rather have boy babies than girl babies.So, when a woman has a girl baby, she loses social status and influence, relative to the status she would have gained by having a boy baby.

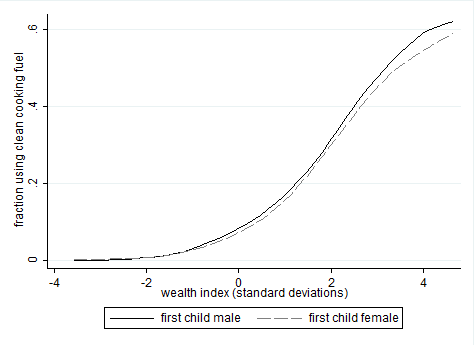

This led to our statistical question: Are household’s where the first baby was a boy more likely to use clean cooking fuel, on average, than households where the first baby was a girl?As the graph below shows, the answer is yes.At all levels of wealth high enough that anybody uses clean fuel, those with a first boy baby are more likely to use it than those with a first girl baby; it never goes the other way.

This suggests that having a boy baby, rather than a girl baby, relatively increases women’s status, leading to the household being more likely to use the healthier fuel.We have a working paper that goes through the argument in more detail and rules out potential problems, if you’re interested.One important fact is that there is no similar effect of having a girl baby on owning any other kind of asset or on having electricity, suggesting that it really is something special about the burden of dirty fuel falling mainly on women.

Unfortunately, identifying this problem tells us little about the solution – other, perhaps, than educating girls in the long run.However, it does suggest that social barriers to clean fuel use could be every bit as important as technological or economic barriers.Designing a fancy, efficient stove for Indian villages might accomplish little if the man who makes the family spending decisions thinks that smoke is the woman’s problem.