If you know what's good for you

— Blog Post — 4 min read

Why don’t I floss my teeth more often? Or go to the gym more frequently? Or eat more green, leafy vegetables? In the big picture, what I do with my health probably doesn’t matter. But, sometimes these little behaviors – or the missed opportunities they represent – add up to something that does matter.

It is a demographic puzzle that Indian people, especially Indian children, are so short. An average eight year old in India (according to my quick computation) is as much as 15 centimeters shorter than international reference heights for healthy children. While some people argue that there could be genetic differences, many people (including me) suspect that net nutrition has a lot to do with it: people are not getting enough good things to eat. I wrote “net” nutrition because what matters is the balance of what you eat (both calories and nutrients) and what you never get to absorb (because, for example, of diarrhea or worms that eat your food before you can).

Diarrhea often comes from hands, food, or water than have been contaminated with feces. A good way to keep that from happening is to wash your hands with soap after defecation. But not everybody does that – as the ubiquitous bathroom signs in U.S. restaurants testify. Why not? Of course, a better sanitation infrastructure would be best, but in the absence of such expensive public systems, could handwashing with soap be a binding constraint on Indian children’s height and health?

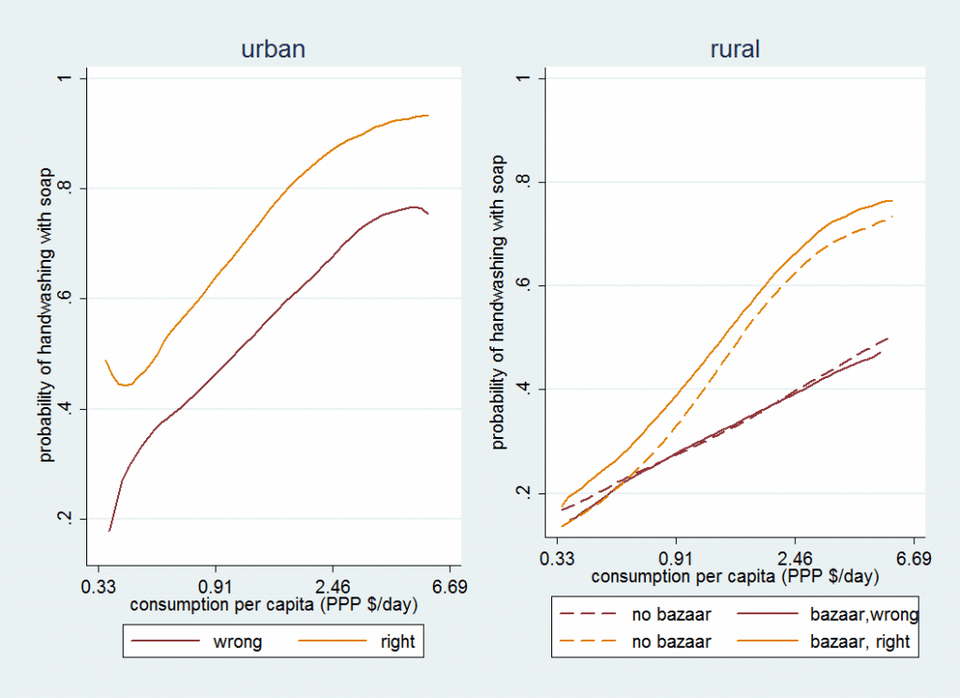

The India Human Development Survey (my new favorite dataset) asks about handwashing with soap. One adult woman from each of 41,000 households, selected to answer education and health questions, reported whether she washes her hands with soap after defecating. The graph below summarizes the exploring I have done in the data so far.

There are at least three reasons you might not wash your hands with soap: affordability (you cannot buy the soap), access (there is no soap to buy, even if you want it), and desire (do you think that you should use soap?). The first conclusion – from the upward slope of each line – is that affordability matters. As people get richer they are more likely to use soap, and few of the poorest rural people use soap, no matter how you slice up the data.

Access is more complicated. There is much more soap use in urban than in rural places, which could be because shops are everywhere, or could be because people there have different preferences. Yet, I have visited many rural Indian villages: I almost always look for soap for sale, and when I do I always find it. In this graph, for rural households, I have separated out those villages that have a bazaar to shop at from those who do not: this indicator of access makes almost no difference. There is similarly no effect of contrasting villages that have a pharmacy with those that do not, or women who are allowed to carry their own cash from those who are not. Physical access, on average, may not be a binding constraint.

Desire – or, more precisely, knowledge – seems to be very important. A separate part of the survey asked the women whether they should give a child with diarrhea more, less, or the same amount of fluids. On the graph right/wrong indicates giving the right answer (more fluids) or a wrong one. Women with this health knowledge were much more likely to report using soap, suggesting that understanding disease is part of the problem. I found a similar picture looking at general literacy, rather than this question in particular. Moreover, in rural India, income looks more important among the women who got the question right. This is consistent with an interaction between affordability and knowledge: not being able to afford soap only matters if you want it.

I started out talking about desire, and ended up talking about knowledge. Was that a fair switch? Implicitly, I was suggesting that whether or not you would want soap has a lot to do with whether you know that it could keep you or your children from getting sick. But, as Timothy Burke found in fieldwork in Zimbabwe and as the shareholders of Bath and Body Works have long known, people buy soap for many reasons (luxury, fun, social pressure, habit) that have little to do with hygiene.

One unfortunate puzzle is that members of India’s lowest-ranked castes and “scheduled tribes” – two socially excluded groups – are less likely to wash their hands with soap and to get the diarrhea question right. This is true even after statistically adjusting for differences in wealth, education, village remoteness, and household demographics. These groups are regularly and regrettably described as “backwards” even by sympathetic analysts, reflecting the perception from the cities that these folks just do not know what is good for them. (Recall the Tamil Nadu nutrition project I wrote about last week.)

With such a rich data base, one of my next steps will be to try to understand exactly where this difference comes from. Maybe it is just a difference in knowledge and preferences. It could be, for example, that these groups do not actually get the chance to learn from ostensibly similar opportunities: for example, maybe the doctor hurries low ranking young mothers out the door, rather than taking the time to explain germs. Or, it could be that even though there are stores in their village, they are socially pressured not to come shop.

So, perhaps health knowledge is an important part of the problem. Yet, even if it is, that does not mean that putting public service posters about germs and soap at every corner is going to do any good. Where do health beliefs come from? From school? From friends? Passed down from mother to daughter? Rural women who listen to the radio more are more likely to use soap, but it is hard to pin down why. It remains an open question exactly why soap use by the rural poorest is so low. It would be interesting to calculate whether buying soap is cheaper, on average, than replacing the nutrients children lose due to diarrhea – I suspect it is.

However, returning to my own bad health behavior, and the bathroom signs reminding us that some Americans do not wash their hands even when the soap is free, it could be more complicated. Orwell, reflecting on the squalor of depression-era England, suggested that poverty encourages fatalism. Elsewhere, I (and others) have argued that being poor depletes the sort of mental resources that help us control our behavior. Being poor might make it harder for anybody to be mindful of the non-obvious ways that little things like washing our hands add up to big things like children’s heights.