A clean village with a messy pradhan

— Blog Post — 4 min read

Starting from where we live in Sudamapuri, you get to the village of Terwa Chilaula by first taking a bicycle rickshaw into Sitapur, the district capital town. Near the main bus stand, turn north along the road to Lakhimpur, the last district before Nepal. A little ways down the road, there will be a massing of “tempos” – three-wheeled, slow-moving vehicles whose drivers charge you about five rupees to cram in to a small space with six strangers and their many children. When no more people can possibly fit – and a young man crippled by polio has found a perch dangling from outside the vehicle – the tempo will putt-putt off over the railroad track and out of town.

Eventually the children will get bored of inspecting you. That’s how you’ll know you’ve gotten there. Climb out the tempo, pay the driver, and walk into the village.

Diane and I traveled to Terwa Chilaula today to check out something that I had read on the internet. According to the official government data on the Total Sanitation Campaign webpage, it is the only village in our home block of Khairabad to have won the NGP: the “clean village prize.” A village wins the prize for building many latrines under TSC and, in principle, for being “open defecation free.” Hunting down Terwa Chilaula would be a good test of the government data that I had been using: if any village would be full of latrines (and many are not), it should be this one.

And it was. There were dozens of them, little brick buildings either freestanding or attached to other buildings, with toilet pans inside for squatting. Most of them had been painted with the label “toilet” and a number from a consecutive numbering scheme that pretty much clinches their government origins. We found them in the richer and poorer parts of town alike, and discovered a painted toilet complex, with a boys’ and girls’ side, in the “downtown” area of the village, near the meeting hall and school.

Better yet, the toilets seemed to be in use. Generally they had a cloth or old piece of a bag hanging in the doorway (a good sign) but not always (still more private than pooping in the open). Sometimes there would be two right next to each other (somebody got a deal) and one of them would be unused, or used for storage. But, on the whole they seemed to be in use throughout the village, and the open spaces that might, in some villages, otherwise smell or look like open defecation didn’t here. Here’s a picture I took of one: notice the signs of use in the pan, and the cup kept on hand for cleaning.

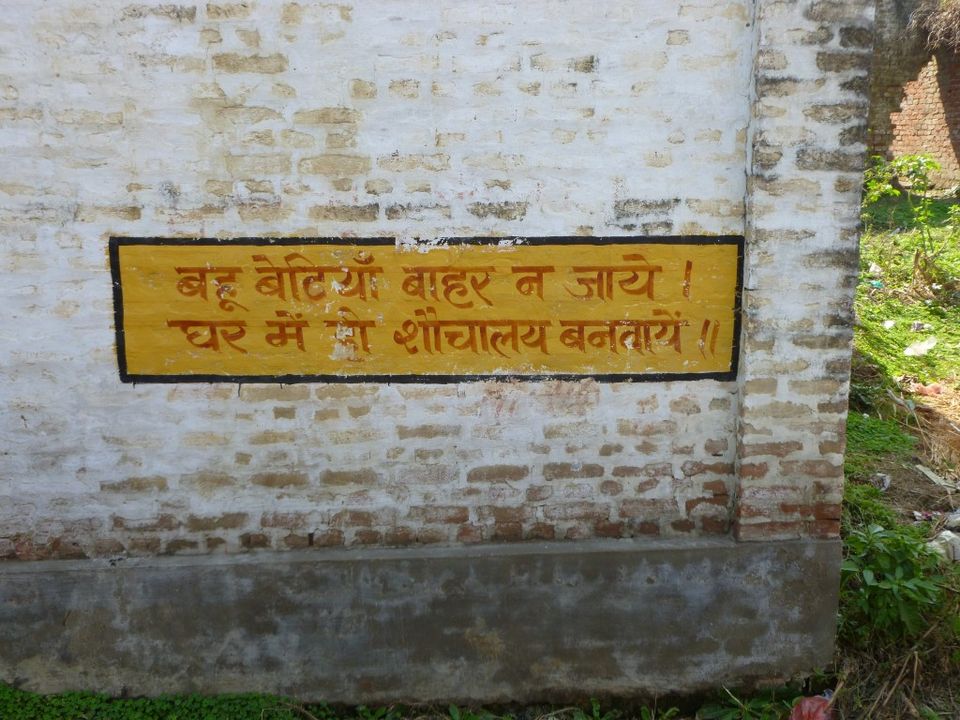

At least some attention seemed to have been paid not to just building latrines, but also to encouraging people to use them. This message had been painted on a wall in a well-traveled area. It roughly translates to “Don’t let your daughters go outside… make a toilet at your house!” I had seen similar exhortations painted on the walls at a village I once stopped at in Madhya Pradesh.

So, we had verified the data, but how did this village get its act together? Why were there latrines there? To find out, we started asking for the pradhan, essentially the village mayor. We were shown to a large, two-story house painted blue to communicate that the family that lived there were of a high-ranking caste. We called out, and some women leaned out over an upper floor balcony. We wanted to meet the pradhan, we explained. No can do, the women replied, all the household’s men are in Sitapur (and, of course, high caste women can’t leave the house, especially to talk with strangers!).

Could we at least have his phone number? This produced an awkward, unexpected, and flat no. Is there someone else we can talk with? They gave us another name.

We found a guy from the family of the name we were given, laying outside his house in his short shorts. He was pretty sure he had a family member who was pradhan at some point, but not while the toilets were built. Those were built in a couple of waves by the government, he recalled, at least five years ago (which matched nicely with the government data). He gave us another name, of a man who used to be pradhan, and now owns a sweets shop on the road back to Sitapur.

So, we made our way back to Sitapur, stopping at about every sweets shop on the way. We finally found the son of our pradhan, who called his father. We waited, and marveled at people’s dexterous use of the hand pump outside of the shop: you have to block the pipe with one hand while you pump with the other, in order to build up enough water to catch in your hands and drink.

The ex-pradhan arrived. We gave our introductions. He knew all about the prize, but he was pradhan way before then. The pradhan at the time of the prize was… of the original family in the blue house.

Defeated, we went home, and happened to chat about our day with our friend and neighbor, a newspaper reporter. Like Jeeves, he knows everything about everybody. We told him the story of our mystery pradhan. Yes! He used to be the pradhan, a few years ago, but the village has cycled through, and now it is “reserved,” required to have a female pradhan. So, the pradhan arranged to make his wife pradhan, and continues to govern the village as before. Chances are, we really did meet the true pradhan, leaning out the balcony of the blue house.

This village was probably pretty special. It was near a big road to the next district, and we saw at least two cars. So, the take-away message is not that the Total Sanitation Campaign is working well all over rural Uttar Pradesh. But it can work, and is working in some places, even in a place with screwy local politics. And – particularly important for my purposes – the government data appears to have at least some basis in reality.